In A World Where Cash Is King, Why Do Non-Profit Theatre Groups Like Manhattan Theatre Club And Roundabout Seemingly Avoid Making A Profit?

Do Non-Profit Theatre Companies Try Not To Make Money?

The phrase “non-profit” seems counterintuitive. How could any business model survive if it doesn’t make a profit? Regarding Broadway theatre specifically, how do organizations like Manhattan Theatre Club and Roundabout stay afloat? In short, operational funding comes from donations, memberships and federal and municipal grants. Given that these companies don’t really have to worry about their bottom line, do they go to great pains not to generate an overflow of income?

There’s compelling evidence to suggest that some of these groups may indeed be unmotivated to rake in the dollars and yet still only cater to the elites.

Selling Tickets Later On Favors The Elite Buyer

For example, even when there’s significant momentum behind a show, Broadway non-profits don’t start selling tickets to the general public until four weeks prior to opening. Now, that may be in the best interest of their subscribers, who pay to get early (and sometimes exclusive) access to productions and events that may otherwise sell out. In essence, that seems fair.

Subscription members are loyal consumers who pay their dues in order to be prioritized. It’s a transactional relationship. But by catering to their members (often elitist and affluent), such institutions are not able to reach the masses. And that’s probably how they like it, bit that does not make it right, especially when public funds are being used to support their activities.

Tourists Get Denied

New York City locals aren’t the only folks who want (or deserve) the inside scoop. The tourist population is still the bread and butter of Broadway business but it doesn’t make sense for them to subscribe to one of these theatre groups because there would be no way for them to see all of the shows in a season.

Visitors also tend to make their plans far in advance so they can fit in everything they want to do on a trip— their schedules are not that flexible. If tickets aren’t available for pre-purchase, say, several months ahead of time, that contingent has no choice but to miss the action completely, pay a last-minute premium via a reseller or hope for a miracle like last-minute house seats or TKTS. Those are poor options and result in less attendance by these groups and non-profit theatre knows that.

Marketing To An Already Loyal Subscriber Base

These non-profits do market their shows but again, their target audience are those patrons already in their pocket: subscribers. And such marketing tactics tend to be traditional like direct mailers. Does Gen Z even know how to open a mailbox?

Lack Of Dynamic Pricing On Tickets

Regarding actual ticket costs, non-profits don’t implement dynamic pricing. In essence, that’s a virtuous practice, one that’s surely appreciated by the average consumer. Whether or not a show is boffo or floppo, prices at non-profits always stay the same regardless of of how well or badly sales are going. But if people can afford to pay more, and are willing to pay more, why not charge more?

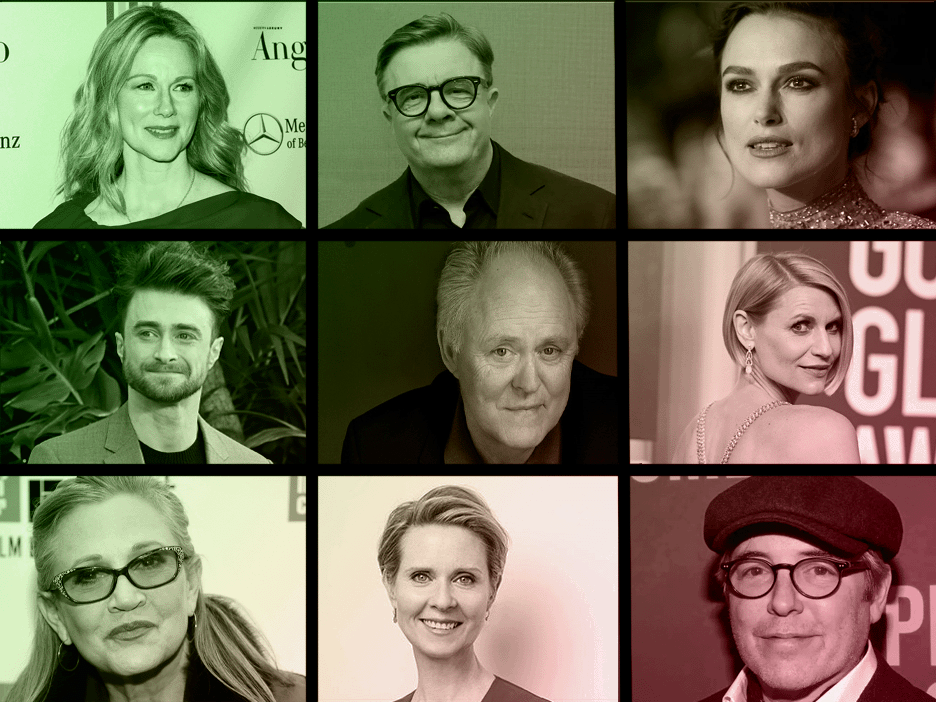

Non-Profits Draw Big Stars

Altering the supply to meet the demand could ultimately increase outside funding. MTC, Second Stage, The Public, New York Theatre Workshop and Roundabout all draw starry casts. Nathan Lane, Laura Linney, Matthew Broderick, Sutton Foster, John Lithgow, Claire Danes, Jessica Lange, Audra McDonald, Carrie Fisher, Keira Knightley, Daniel Radcliffe, Jeff Daniels, Cynthia Nixon, Linda Lavin…the list goes on and on. Why not capitalize on a potentially, exponentially higher revenue stream? Why not forgo the elites and drive new audiences to their theatres? What's wrong with being mainstream?

Yes, this is a more capitalist mindset which may go against the ethos of the non-profit model, but not if they take the long view into account. Generating more money and bringing in more diverse audience can only help preserve a company’s longevity, and the art form of theatre in general. Instead, they hand out hefty commissions to a litany of writers who may take decades to create anything even worth producing. And there’s no guarantee that those projects will ever reach fruition.

Failure Of The Non-Profit Public Mandate

As noted, non-profit theatre companies are funded from a variety of sources. Some of those sources are indeed private foundations. However, some municipal funding comes from taxpayer pockets, many of which are shallow. And yet those taxpayers don’t get the same access as the elite subscriber base does. That’s a complete failure of the public mandate.

The Public Theatre— one of the country’s OG non-profit theatres— had the right idea in theory with free Shakespeare in the Park but in recent years, even that venture has become all about connections or paying people to wait in line— these shortcuts favor the affluent upper class.

It seems that nonprofit theatre companies are failing their public mandate and there isn't anyone at the top of these organizations that cares enough to make a change.